|

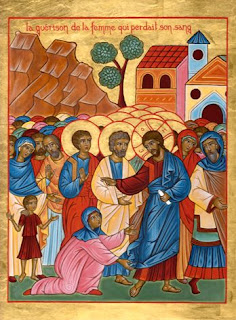

"Love and Life for the World"

2 Kings 4:42-44; Ephesians 3:14-21; John 6:1-21

Do you ever

find yourself wondering what actually happened in these stories we just heard? A man comes to Elisha bringing food from the

first fruits: twenty barley loaves and some fresh ears of grain. Elisha says,

“Give it to the people and let them eat.” But his servant can’t see how that

will be enough. Elisha had heard God’s

promise: “Thus says the LORD, ‘They shall eat and have some left.’

Would you

have believed Elisha?

The Bible

tells us that Elisha served the twenty barley loaves and the grain, and the

hundred people ate, and there was more than enough.

There are

similar themes in the gospel lesson we just heard.

The gospel lesson we just heard is one of the few stories

that John and the other gospel writers tell in common. It’s the only miracle story that appears in

all four gospels. So, it must have been important to the early church.

After this, Jesus went away to the other side of the Sea of

Galilee. The verses leading up to

today’s gospel lesson set the context. The crowds are following because they

saw Jesus perform SIGNS. Jesus has healed the official’s son and a man by the

pool. The amazing things Jesus has been doing create a sense of anticipation for

what is to come.

A

large crowd was following him, because they saw the signs that he was doing on

the sick. Jesus went up on the mountain and sat down with his disciples.

Jesus

looked around at the large crowd and asked Philip, “Where are we to buy bread,

so that these people can eat?

John

tells us that Jesus said this to test Philip, as he already knew what he would do.

Philip

answered Jesus, “Two hundred denarii worth of bread wouldn’t be enough for each

of them to get a little.”

Then Andrew said, “There’s a boy here who has five barley

loaves and two fish--but what are they for so many?” Andrew sees the possibilities, but he’s still

concerned that they don’t have enough.

Jesus

said, “Have the people sit down.” John

mentions that there was a lot of grass in the area, which made it a comfortable

place to sit down and have a picnic.

There

are four gospel stories that tell about Jesus feeding 5,000, and Matthew’s and

Mark each add a similar story about Jesus feeding 4,000. In all six stories, there

are lots of left-overs!

At the

center of the story is a miracle.

Now, if I

were to tell you that it happened exactly the way the story says it

did, some of you might get a

little cranky. Some folk have a hard time believing

that sort of thing… or would tell us that nothing like that has ever happened

to you.

The way some people get more comfortable with

this story is to explain that of course many of the five thousand people had a

little food tucked away in their tunics—something they planned to sneak off and

eat by themselves—but that Jesus got them to share what they had, so that there was

plenty for everyone, with twelve baskets left over. According to that kind of thinking, the MIRACLE

is that Jesus got them to share.

I think that

interpretation has some merit, and it’s helpful to some folk who struggle with

how to interpret the miracle stories in the Bible.

But that’s

not what the Bible says. and that when

the people saw it, they knew who he was.

They understood the feeding of the five thousand as God’s divine hand in

human affairs—God’s supernatural interruption of the natural order. There was bread where there hadn’t been any

bread…fish where there hadn’t been any fish.

That proved who Jesus was to them…and established their faith in

him. The miracle made people

believe. It gave them faith where

there had been no faith—the same as it gave them food where there had been no

food.

I’m not

going to try to tell you how it happened that Jesus was able to feed thousands

of people that day in the Galilee, because I can’t explain it in a pat,

rational way that would satisfy everyone.

But I believe the gospel writers when they say that something amazing

and extraordinary happened, and that many hungry people got fed-- when it

looked like there wouldn’t be enough. In

the midst of what looked like scarcity, there was abundance!

I think it

was C.S. Lewis who said that a miracle is something that takes your freedom

away along with your doubts… something that leaves you no choice but to

believe. You witness a miracle—or, as

John the Evangelist would say, a "sign"-- and it makes you have

faith.

But I’m not

so sure about that. Without faith, there

are always other explanations for even the best of miracles. You say you heard the voice of God? It sounded like ordinary thunder to me. She was healed of her illness? It was probably psychosomatic in the first

place.

Come to think

of it, though, is there proof for anything that really matters in the

world? Are there homegrown, ordinary miracles

you can think of—that there’s no evidence for… nothing that could prove them to

anyone else…or to you—if you didn’t believe in them first.

Could it be

that we’ve gotten it all backwards somehow?

Maybe faith doesn’t come after miracles—but before them? Perhaps what makes something holy--what

makes it a glowing and life-giving wonder—isn’t something about it…but about us.

In today’s

gospel lesson we hear echoes of the Passover-Exodus story. Chapter five ended

with complaints about a shallow, superficial understanding of Moses. But

chapter six intends to show a deeper, fuller understanding of Moses and the

Passover, which is now revealed in Jesus.

When Jesus

miraculously feeds the multitude in the wilderness, the people remember the

promise that God will raise up a prophet like Moses, and they confess that

Jesus is that prophet. What they fail to realize what this sign actually

reveals. Instead of seeing in Jesus the embodiment of God’s glory, love, and

Word, they see a king…a political or military figure they hope will serve their

desires. The crowds are missing the point of what’s happening. They see Jesus’

gracious gift--but they want him to manifest a glory that fits into their

assumption and serves their goals.

How often

do we fail to see the depths of what God is doing, because we’re focused on

what serves our desires? How often do we fail to realize how graciously God is

acting among us, for our sake and for the sake of the whole world?

We only see

partially and in distorted ways. We need the continuing word of Jesus and the

gift of his presence, if we are to move more deeply into God’s glory.

When the

story moves to the next scene, we hear more echoes of Passover.

Jesus,

knowing that the people in the crowd wanted to make him king by force, had

withdrawn again to a mountain by himself. Then, when evening came, his

disciples went down to the lake, where they got into a boat and set off across

the lake. A strong wind was blowing, and the waters grew rough. When they had

rowed about three or four miles, they saw Jesus approaching the boat, walking

on the water…and they were frightened.

But Jesus

said to them, “It is I. Don’t be afraid.”

Or, more accurately, we could read Jesus’ response as “I am.” “I am” and

“Don’t be afraid” are the language of theophany.[1] I think Brian Peterson is right when he

suggests that, in John’s language, it’s a “sign,” a window into the glory of

God present in this world through Jesus.[2]

Like the

crowds in John 6, we have been fed by God’s grace and mercy and care and

steadfast love. Like them, we often fail to see what God is doing among us. We

look for a Messiah or king who will serve our desires or our agendas.

But God is

up to something far greater than anything we could imagine. Jesus comes to

dwell among us, full of grace and truth, to reveal to us God’s love. Jesus

comes across the fearful, lonely, empty, dangerous times and places and says,

“Don’t be afraid. I am.”

He calls us

to feed the hungry--to provide food and clean water to those who lack the basic

things of life. But we look around and we’re afraid that our resources aren’t

sufficient to meet all the needs. We’re

afraid there won’t be enough.

Perhaps part of the miracle of our life of faith is that we

creatures are able to make use of our freedom:

to believe in spite of our doubts…to have faith without proof…and that because

of those capacities in us, miraculous things do happen from time to time. Some of them are extraordinary. But most of them as ordinary as the voices of

our fellow human beings telling us that we are loved…that we are precious in

their sight and God’s…that they want to link their lives with ours…that together

we can, with God’s help, change the world.

Together,

we can practice trusting in God’s abundance and grace. Together, we can receive

from Jesus’ hand what he gives and go out into the world with the gifts.

All life

and all good gifts come from God. Jesus keeps coming to us to open our hearts

and our hands to those around us…to open our eyes to his presence. He keeps

encouraging us: “I am. Don’t be afraid.”

In the epistle lesson we heard, we hear Paul praying that

the church, according to the riches of God’s glory, “may be strengthened in your inner being with

power through God’s Spirit, and that Christ may dwell in your hearts through

faith, as you are being rooted and grounded in love… that you may have the

power to comprehend, with all the saints, what is the breadth and length and

height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, so

that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.”

As Gentile

readers of the twenty-first century, do we get it? This message is for us, no less than to the

ancient church in Ephesus. God has a

plan for us, for us to be strengthened in our inner being with power through

God’s Spirit…for Christ to dwell in our hearts through faith…for us to be

rooted and grounded in love…for us to be filled with the fullness of God. We come together to be fed…filled…to open our

lives to God in prayer…and to be transformed by God’s power.

Do we believe

in that kind of miracle-- the kind of miracle in which we believe enough in

God’s grace and power to risk giving our lives in prayer?

The GOOD

NEWS is that—if we give our lives in prayer—we can begin to comprehend that God

is within and around us. We’ll begin to

see ourselves and everyone else differently.

When we give ourselves in prayer, we begin to see the world in terms of

God’s economy of abundance. When we give

ourselves in prayer, I believe the things that break God’s heart break our

hearts too…and we begin to comprehend what Jesus meant when he said, “How

blessed are those who mourn! How blessed

are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness! How blessed are the peacemakers!”

When we’re

weary from responsibilities with family, work, and church, the vision of God

leads us back to the way of love and LIFE.

When we

pray, God gives us the courage to risk.

We learn to trust not in ourselves, but in something far bigger than we

are. We live with what Brett Younger

calls “a muffled but persistent sense of the holy.” [3]

What kind

of a miracle might we experience if we pray for a bigger vision of God? What kind of a miracle might we be a part of--

if we pray that we will see our life in the center of God’s goodness…that

Christ might dwell in our hearts? What

kind of a miracle might it be if God overwhelms us with grace and it overflows

in our lives and makes a difference in the world?

So… let us

pray for faith in God’s power working in our world and in our leaders. Let us pray for God’s power in us to do

everything that we can do to stop terrible hatred and violence in our world. Let there truly be peace on earth, and let it

begin with you and me.

Now, to the

One who by the power at work within us is able to accomplish abundantly far

more than all we can ask or imagine, to God be glory in the church and in

Christ Jesus to all generations, forever and ever.

Amen!

Rev. Fran Hayes, Pastor

Littlefield Presbyterian Church

Dearborn, Michigan

July 29, 2018

[1] Exodus

3:14; Isaiah 43:10, 25; 4`:12; Genesis 15:1; Exodus 14a;13.

[2] Brian

Peterson, Commentary on John 6:1-21 at https://www.workingpreacher.org/preaching.aspx?commentary_id=3749

[3]

Lectionary Homiletics, July 30, 2006, p. 80.